Credit RGS

Credit Glenn Bartley

Credit RGS

10 Quick Facts Ruffed Grouse (Bonasa umbellus)

1.It is a medium-sized grouse found in forests from the Appalachian Mountains across Canada to Alaska.

2.It is non-migratory and the only species in the genus Bonasa.

3.The ruffed grouse is sometimes incorrectly referred to as a "Partridge" an unrelated, phasianid and occasionally confused with the Grey Partridge, a bird of open areas rather than woodlands

4. The genus Bonasa was applied by British naturalist John Francis Stephens in 1819

5. These chunky, medium-sized birds weigh from 450–750 g (0.99–1.65 lb), measure from 40 to 50 cm (16 to 20 in) in length and span 50–64 cm (20–25 in) across their short, strong wings

6. Ruffed grouse have two distinct morphs grey and brown. In the grey-morph, the head, neck and back are grey-brown.In brown-morph the birds have tails of the same color and pattern, but the rest of the plumage is much more brown, giving the appearance of a more uniform bird with less light plumage below and a conspicuously grey tail

7. The ruffs are on the sides of the neck in both sexes. They also have a crest on top of their head which sometimes lies flat. Both genders are similarly marked and sized making them difficult to tell apart even in hand.

8. They are omnivores eating buds, leaves, berries, seeds, insects along with salmanders and small snakes.

9. Females may also do a display similar to the male

10. The ruffed grouse population has a cycle, and follows the cycle no matter how much or how little hunting.

Grouse by Dave Hughes

Habitat and Habits by the Canadian Wildlife Federation

The Ruffed Grouse is common throughout most of Canada. It does not migrate and, once established, lives all its life within a few hectares. Its large size, rich colours, and the explosive burst with which it takes flight are distinctive.

It is found wherever there are even small amounts of broad-leaved trees, especially poplars, birch, hop-hornbeam, and alders, which provide the catkins and buds that are its staple winter food. The deciduous trees, important as food and shelter to the Ruffed Grouse, frequently occur in the early stages as forests grow back after logging or forest fires. It is likely that there are more Ruffed Grouse now than before European settlement, because much coniferous forest has been cut or burned and succeeded by aspen and other trees favoured by grouse. In many areas the increase in Ruffed Grouse has been at the expense of Spruce Grouse, a conifer-loving relative.

The Ruffed Grouse is adapted to a life in hardwood bush and forest. Its well-adapted beak, legs, wings, and gut permit it to feed by browsing on buds, leaves, and twigs. The bird is an excellent climber among slender branches and on thin, yielding stems. Essentially a ground dwelling bird, the Ruffed Grouse is also expert at short, rapid, twisting flights and can actually hover and make complete turns in the air—all useful traits for flying through thick bush.

A good winter for the Ruffed Grouse is one with soft, deep snow that lasts. If the snow cover is inadequate or has a hard crust, or if there are long periods of cold and wind, grouse cannot find enough suitable protection. They are forced to seek shelter in clumps of thick conifer. Under these conditions grouse lose weight and many fall prey to hawks and other predators. Some grouse may starve; others freeze to death.

Male and female Ruffed Grouse live separately. The male establishes himself among other male grouse by drumming and fighting. He stays on his territory throughout his life, chasing other males away and courting females on the areas occupied by established males. The male’s display—or drumming—post, on which he drums to warn other grouse away and to attract female grouse, is often atop a large moss-covered log at the edge of a forest opening. Near these display posts, males find all the necessities for life, such as roosts, shelter from weather and predators, food, and places to dust bathe.

The hens live alone throughout the forest, but they do not display themselves, and they move over a larger area than the males. Wildlife biologists who have attached small radio transmitters to the backs of hens have found that the hens cross trails with each other and may travel through the territories of several males.

Breeding

Spring is mating time. The hens must find the food they need to produce good eggs that will result in healthy young. When they are ready to mate, hens are attracted by a drummer and will mate with him. Both males and females mate with any grouse that presents itself at this time.

After mating, the hen selects a nest site, which may be some distance from her mate and even on the territory of another male. Her nest is always on the ground and usually at the base of a tree, stump, or rock, close to an opening and in forest that provides shelter.

The nest is simply a shallow bowl in the ground, lined with whatever materials are at hand and feathers from the hen. After laying seven to 12 eggs, she incubates them, or keeps them warm, for 23 to 24 days until they hatch, usually in early June. Only one clutch, or set of eggs, is produced a year, although some hens will lay again if their first set of eggs is destroyed early in incubation.

A nest of eggs, once discovered, is easy prey for a number of birds and mammals that take the eggs for play or food. The hen will sit motionless on her nest almost until touched. She usually leaves the nest to feed in the early morning and late evening, when the uncovered eggs are hard to see. This behaviour and her camouflage of plumage are most effective; very few nests are destroyed.

The hen leaves the nest with her brood of young within a day after they have hatched. The brood may travel a long distance before settling down to live on a relatively small brood range that provides shelter and abundant food.

The hen and chicks behave in many ways that protect the young, particularly before they can fly. For example, when startled by intruders the hen distracts attention from her chicks by hissing, clucking, and dragging one wing as if it were broken. She appears quite helpless and a ready meal. Try to catch her and she bursts into the air and flies away. Meanwhile the chicks remain immobile on the forest floor.

Throughout the summer the chicks grow rapidly in size, weight, and plumage. They feed heavily on insects at first but will always take succulent vegetation. By August, they enjoy a variety of flowers, soft leaves, berries, and seeds. Clover is particularly attractive to young grouse. Many are taken by hawks and hunters while they feed on this plant along roads through the forest.

The early mortality of grouse chicks may be very high. Within a week or two of hatching, half of the hens may lose all their young, and the remainder may have broods about half the size of the clutch. Studies suggest that the early mortality may be largely due to the type of eggs produced by the hen. This, in turn, is influenced by her diet in winter and early spring, which provides the food reserves for unhatched chicks.

Other causes of mortality in young grouse are accidents, predation by enemies, including foxes, Northern Goshawk, and the Great Horned Owl, and diseases, such as a damaging stomach worm Dispharynx, which grouse pick up when they eat wood lice. Very rarely are any diseases of grouse harmful to humans.

Starting in June, the adult birds gradually moult, losing and replacing all their feathers. It is not unusual to see a grouse in late June with no tail. The chicks replace their natal down with a rough, poor quality juvenile coat, then replace this with the yearling plumage by 16 to 17 weeks of age. This plumage is generally similar to that of the adults.

In autumn, when the young are almost fully grown, there is another period of relatively intense activity. Males begin to drum again, and young grouse disperse throughout the forest, seeking a place of their own to live. Some may establish themselves on the territories of old birds that have died.

The established birds are secure because they have obtained a place that will provide food and shelter from weather and predation. The displaced grouse, usually young, are forced into habitat where food and cover are inadequate, and more of them die in winter. In winter, broad-leaved foliage is much reduced or eliminated, exposing grouse to predators as well as forcing them on to their staple winter diet of buds and twigs.

Grouse Diseases

DISPHARYNX PARASITISM/PULMONARY MYCOSIS/AVIAN TUBERCULOSIS

Study by Alfred D Gross

Eastern Equine Encephalitis Virus

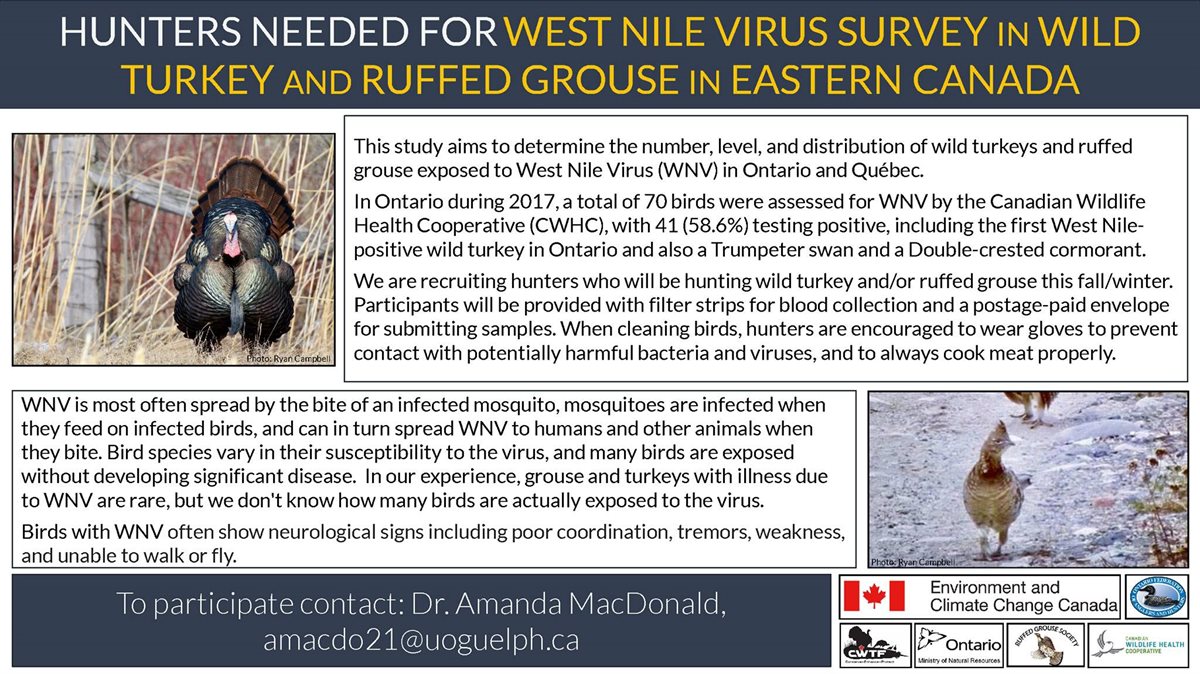

West Nile Kit Information